Down On The Test Farm

Testing any software suite as complex as NTPsec is difficult. The intrinsically time-varying quality of NTP’s operation makes it much more so. In some future post I’ll probably write about my only real failure on this project, an attempt to enable time-invariant replay testing that failed for specific technical reasons very peculiar to NTP.

Just because we can’t have that doesn’t mean we get to punt the test problem - we can’t slough that off, not for core infrastructure that needs to be super-reliable. Pieces of NTPsec have unit tests; sadly, those aren’t very good at exercising most of the code complexity. But even when replay testing can’t work, and unit testing doesn’t have the coverage you’d like, there are still useful approaches. One that is especially applicable to service daemons like ntpd is to simply run the software a lot, continuously, for long periods of time, watching for crashes, anomalies, and resource leaks.

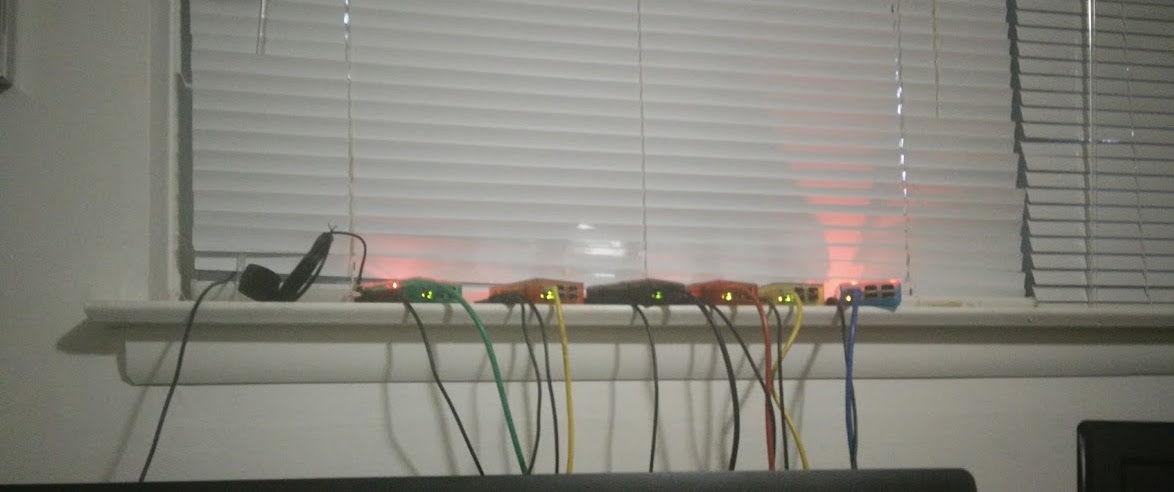

That is why NTPsec has a test farm. It consists of 7 Raspberry Pis, each equipped with a GPS daughterboard, hanging out on the Official Windowsill of Mad Science above my desk.

Why Raspberry Pis, rather than more conventional PCs or VMs somewhere? One major reason for preferring physical hardware is that it’s tough to put a GPS daughterboard on a VM. RPis have the advantage of being small, cheap, and almost disposable. The entire test farm, 7 Pis with all the trimmings (8-port USB hub, 8-port Ethernet hub, cables, cases, daughterboards, stick-on heatsinks, a small diagnostic monitor, and a USB temperature sensor) came in a bit over $800.

To put this in perspective, compare the cash, space, heat-emission and hassle costs of a conventional 7-machine rack-mount setup. It’s hard to see getting away with a bill much less than an order of magnitude higher. Ephemeralization is your friend!

Another reason for preferring small, low-power machines is that I have my eye on embedded and low-power deployments elsewhere. If NTPsec can run gracefully on a Pi, it can run pretty much anywhere.

Your practical tip for today: Avery 4312 "Multi-Use Labels" are almost as large as they could possibly get and still fit on a micro-SD card. Each Pi has a two-letter name taken from the abbreviations for chemical elements; I put that name on each machine using a label-tape printer, then duplicate it on a label on the SD card.

Someday that 8th slot will be occupied with a different hackerboard, likely some flavor of Beaglebone. I actually experimented with an ODroid C2 at one point, but some of the hardware interfaces I needed for a GPS daughterboard (serial UART, 1PPS) were absent or undocumented.

When I first deployed a couple of Pis for testing I had an unusual environmental problem: our cat. Zola used to like to hang out on what is now the Official Windowsill of Mad Science, and while he is generally a very well-mannered and non-disruptive creature, all cats are inveterate physicists. We know this because they’re constantly seeking to refine their measurement of the gravitational constant by performing drop tests.

This would, of course, have been quite the unhappy outcome for the RPis. Which is why at one point I thought I was going to have to put a bunch of Legos on the project budget. As the University of Southampton has shown, a Lego enclosure makes a dandy lightweight protective rack for RPis; that and a bit of double-sided sticky tape to secure it would, I thought, nicely solve my cat problem.

I got as far as trying to bring up a Lego CAD program to design the rack with, then stalled because the thing’s UI was not really very good. While I was nerving myself for another try the windowsill filled up with more machines and Zola lost interest in hanging out on it.

Oh, and the farm’s results? They are, so far, wonderfully boring. Pushing nine months of near-continuous operation (except for software refreshes and the odd power outage), with no crashes, no unexplained anomalies, no nuthin'. As the fabled wizard Rincewind once observed, sometimes boredom is good. Any software engineer could do with more such boredom in his life.