From Steak to Sizzle

One of our major development pushes, now drawing to a close, was to move as much of the NTP code out of C as was practical to some other language. The point of this was to banish buffer overruns, stale-pointer bugs, resource leaks, and all the other ills C is heir to. These are huge maintenance drags, and fertile sources of security problems.

The NTP daemon itself still needs to be in C, or in some compiled language at least as fast as C, because it’s doing some soft-realtime things and needs to react at machine speed. But most of the auxiliary tools don’t need to be, because they only need to look fast to humans rather than other software and machines. And programs that don’t need to be in C should not be.

Thus, we’ve moved ntpq, ntpkeygen, and (most recently) ntpdig from C to Python. The ntpq program is useful for examining and hot-configuring a running ntpd. The ntpdig program (formerly known as sntp) is a very simple NTP protocol client sometimes used in situations where one-shot time syncing suffices and the full weight of ntpd is not required. The ntpkeygen program is used to generate cryptographic keys for authenticated NTP connections.

We moved these to Python, rather than some other random scripting language, because (a) our build engine is implemented in it, minimizing additional dependencies, (b) I like Python and am comfortable in it, and (c) it seems a safe choice as a language for long-term infrastructure, not a fad that will dissipate in three years.

Doing this move replaced over 10KLOC of C with about 3KLOC of much cleaner, clearer Python - a good thing in itself. It also presented another opportunity. ntpq and ntpdig had been written at different times by different people. Both are clients for variations of the NTP packet protocol. In both, the network-protocol back end was unhealthily entangled with the application-specific front end.

During the Python rewrite, one of my goals was to factor out that back end, cleanly separating it from the front-end logic. The NTP protocol handling and various other re-usable parts became a loadable Python module. The specific parts of ntpq and ntpdig became much smaller and lighter, easier to maintain and extend. In the end, the shared back-end came out to a smidge less than half of that 3KLOC.

And… that back end amounts to being a construction kit for easy and rapid development of new NTP protocol clients. I demonstrated this by requiring only a few hours to write another one.

Two people on the NTPsec team (Gary Miller and I) have prior experience with another project, GPSD. One of the tools that project ships is called "gpsmon". It’s a diagnostic tool for examining the output from a running GPS and (for some types) changing various control and mode settings. It’s what’s nowadays called a "TUI" -Terminal User Interface program, meant to run in a terminal emulator but with a visual full-screen interface.

TUIs are a good interface-design pattern for diagnostic tools that should run fast and light. When Gary suggested that we do an equivalent of gpsmon for NTP, I liked the idea immediately. I envisioned a handy, self-updating status display for time-service administrators - something a bit more modern in flavor than the extremely old-school and rather clunky command-line interface of ntpq, but without the overhead, library dependencies, and complexity of a full GUI.

Gary’s suggestion also answered a question that had been vaguely bothering me for some while. We have made many improvements in NTPsec, but they’re not tremendously visible from the outside. People who sell things have a saying: "Sell the sizzle, not the steak!" Even the best products need a visible hook, a focus that makes people say "I want that!". I had been wondering what NTPsec’s sizzle was going to be, and Gary offered me a potential answer. I went to work with the technical goal of demonstrating the reusability of the Python protocol library, and the marketing goal of making us some sizzle.

That Python back end factored out so much work that the proof-of-concept version of ntpmon took me only about 45 minutes to write. To date the front end has consumed probably less than eight hours of development time and is barely over 300 lines of code, and yet is a fully production-capable tool that many time-service administrators will likely want to have running constantly where they can glance at it. In fact, one of our buildbot wranglers remarked on IRC a few days after first release that he found the effect almost hypnotic. Sizzle achieved!

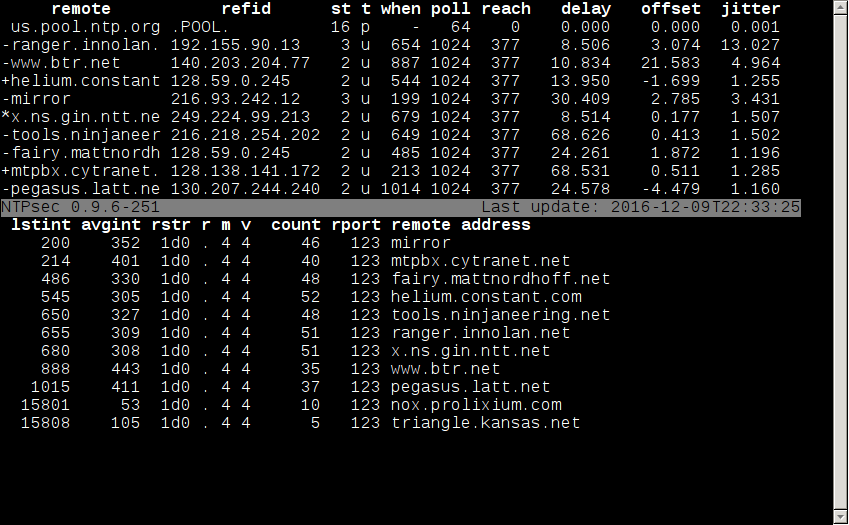

Here’s a screen shot:

Top window is a peer status report, bottom an MRUlist that tells you where the heavy traffic is hitting your server from. The status line tells you how fresh the report is. The tool samples at half the shortest poll interval seen in the last peer list. There are handful of single-character commands to vary the report format, and a help screen.

Here are a couple of the touches that make ntpmon sizzly. When it sees that any host is in INIT mode, it pegs the poll interval to 1 second. Thus, by launching it right after ntpd startup or restart, you can actually watch your ntpd sync to pool servers in near real time.

Also, any keystroke interrupts the wait portion of ntpmon’s main loop. So anytime you press Enter, status update - numbers jump. Instant gratification! There’s enough monkey in humans that just having this action-reward feature in the interface is sizzly, and would be even if the numbers had less meaning than they do. It works on me, even though I knew what I was doing when I wrote it.

I haven’t yet figured how to add color to ntpmon in a useful way, so I haven’t tried yet, despite the fact that color is very sizzly. There’s a point of balance in these matters; sizzle is good, but dignified restraint is classier than superfluous flash.

Notice how I moved from talking about nuts and bolts to the psychology and esthetics of interface design? I could jump up to that level because correct factoring of the code made experimenting cheap and a concept driven outside-in from UI design - rather than inside-out from the details of the protocol - feasible.

This is what code reuse gets you when you do it right. It’s also an excellent demonstration of why not to write in C if you don’t have to; in that language, an ntpmon equivalent would doubtless have taken far longer to write, and been far more fragile when it was done.

I don’t know what kind of NTP protocol client there will be demand for next. I do know that it’s better to have the option of writing them quickly and easily than not — if only because it lowers the cost of exploring the design space.